If students don’t know the story of their course, do they really understand what they’ve studied at all?

This deceptively complex question has occupied much of my thinking

as we approach A-Level revision season.

It’s tempting to view “knowing the story” as a question of

“knowing stuff”. So long as students have revised the details, they know what

happened overall. And if they know that, they therefore know the story.

But having lots of detailed knowledge does not necessarily

mean students can zoom out and see how it all fits together. Plenty of diligent

students end up mastering the finer points of their courses only to find

themselves lost in a sea of information (or, to mix metaphors, unable to see

the wood for the trees).

This was the situation one of our A-grade students found

herself in last year. In a fit of anxiety, she asked me how on earth she could

pull all the information together so she knew the sequence, chronology, and

meaning of the many events she had studied. Thankfully, this student was

self-aware enough to raise her concerns two months before the exam (rather than

two days before). We had time to develop an approach. And, broadly speaking, it

worked. She mastered the story of the course, was able to recognise and

remember how everything fitted together, and got her grade A.

This post explores a series of solutions we developed ahead of last year’s A-Level exams and have continued to work on ahead of this year’s exams as I’ve gone back to refine revision strategies. In what follows, I’ll present this as an integrated approach that might also help your students as they approach final A-Level history exams. This fits into a series of posts (see here, here, and here) since last year on this blog which have explored revision strategies and techniques.

Deliberate

Practice as Grounding Principle

The grounding principle for this approach is deliberate

practice, that is, constructing a range of discreet but interrelated tasks

that through “attention, rehearsal and repetition” facilitate the development

of specific “knowledge and skills that can later be developed into more complex

skills.” (A useful summary of “deliberate practice” can be found here.)

Drawing on this principle, the approach outlined here is

designed to help students see how discreet pieces of information fit together

into a wider “big picture” story or narrative. It requires them to repeatedly

perform a series of tasks, each one enabling the development of a different skill

or aspect of knowledge.

These tasks focus on several skills and processes:

- deconstruction of meta-narratives (disaggregating events from a single “big picture” story or narrative);

- sequencing and chronology (creating ordered chains of events and setting those events to dates);

- periodisation (collating discreet events into distinct time periods);

- classification (sorting events into thematic categories).

In a more fundamental sense, the approach overall asks

students to repeatedly deconstruct the “big picture” into fragments and

reconstruct it in multiple ways, in the process memorising it and finding different

layers of meaning within.

Drawing

Together the “Big Picture”

By the time our student last year had approached me for

help, the first part of this approach was already in place. I had recently

written up a “big picture” narrative which told the story of our course (Russia

and the USSR, 1855-1964) in two A3 pages.

|

| Year 12 content on one page |

|

| Year 13 content on another page |

The task of drawing up these narratives is tricky and might

seem daunting. But it is hugely valuable to both teachers and students. For us,

as teachers, it can provide clarity as to the messages we want to communicate

to students and weave through our lessons, as well as highlighting any areas

for our own subject knowledge development.

For students, a two- or three-page summary of the course

provides a firm grounding for any final revision, and a starting point for

grasping the complex sequence of events and chronology.

Sitting down with lesson materials and the bullet-point

exam-board specification in front of me, I produced a story which is not

riveting in and of itself. It isn’t meant to be. Instead, I sought to pull

together all the core content into one narrative piece that allowed a

zoomed-out overview of the whole course. The text is held together by three broad

principles:

- it refers to all the content required by the exam board;

- it moves chronologically from start to end;

- it is held together by a larger implied question, which had also framed my teaching of the course through Year 12 and 13 (“How did Russia go from being one of the most backward countries in Europe in 1855 to, whatever its flaws, its most powerful and advanced by 1964?”).

Breaking

It Down Again

Oh, how easy teaching would be if we could simply drop written

information in front of students and expect them to remember and comprehend it!

Given this is not the case, I was keen to challenge students

to break down the “big picture” I had given them into workable chunks which

would then form the basis of practical revision activities before their exam.

Firstly, I asked students to identify the major events and

developments covered in the text and categorise them by what we refer to as the

four “themes” of the course – politics, economy, society, and culture.

Secondly, I proposed that students take these events and

developments and commit them to a set of flash-cards (which I dubbed “sequencing

cards”), with the name of the event on one side and (possibly) the date on

the other. (I’ve become much more hard-line in this approach this year;

students are not being given the “option” of creating these cards and will

simply be told they have to produce a set of their own!)

|

| Examples of students' own sequencing cards (2023-24) |

Why ask students to create their own resources? In short,

because this is a key part of their processing of the story of our

course. By first identifying the events to include and then producing the

resources themselves, they are actively engaged from the very start in a (de-

and re-)construction thought process essential to fully comprehending the

bigger picture.

That said, I made sure that students were provided with a

model of what this might look like. In our very first revision lesson, I had

presented them with a set of 48 cards which they had to put in order. At this

early stage of revision, to nobody’s great surprise, they weren’t very good at

it. That was partly the point – to demonstrate to them what gaps in their

chronological knowledge they had and their need for further practice. We went

on to repeat the activity with my cards several times in the 6-or-so weeks of

revision lessons we had in total.

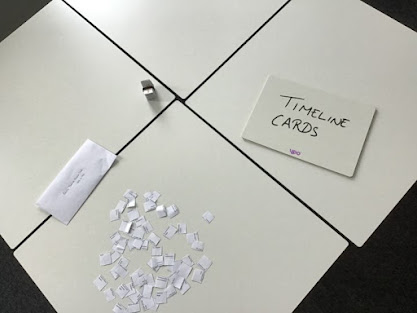

|

| My card sort to model the process |

This all comes with an important caveat. If students were to

adequately cover the course content, they had to go beyond “big picture”

story I provided them, using additional resources including revision notes they

had been making from course booklets since September of Year 12. This is vital

to note, since turning the course into a two-page narrative necessarily meant skimming

content (the point of the “big picture” story, after all, is to provide a

narrative overview, not every granular detail). Those students who did create

their own sequencing cards frequently found they had produced many more than in

the original card-sort task I had given them at the start of revision.

Why

“Sequencing Cards”?

At this point, it’s worth dwelling on the form of the

activity. Why “sequencing cards”?

Firstly, I wanted students to end up with a resource

which they could actively use, rather than passively refer back

to. In the past, I’d probably have suggested they draw out a series of A3 timelines.

As I’ll discuss below, I think timelines do have an important role to play

later on. But in terms of a starting point, timelines have the drawback that,

once created, they remain static on the page. They are therefore more likely to

be glanced at or read back over. By contrast, a set of cards can be taken out,

put in order, checked, corrected, reshuffled, and put away again before the

whole process is repeated. This is altogether a more active, challenging, and

testable activity.

Secondly, in terms of its focus, the key aim of the

activity (as the name reflects) is to sequence events. That is, placing

events in relative order to one another in the form of a sequential chain. Why

does this matter? Rather than obsessing over dates (as many students do) in the

first instance, I was keen for students to recognise the interrelationship

between different events and developments.

This seems to me to be fundamental to the task of mastering

the big picture, since in order to make sense of a wider narrative of events,

students need to be able to draw out causal and consequential links between otherwise

discreet moments in time. In other words, they need to be able to recognise

that certain events fit in at certain points because of the impact they

had on, or received from, other events.

To give a concrete example, the Crimean War necessarily

came before Tsar Alexander II’s Emancipation of the Serfs, not just because the

former happened between 1853 and 1856 while the latter was in 1861, but also

because the Emancipation of the Serfs was seen by Tsar Alexander II as a key

requirement to improving Russia’s military and economy after the Crimean War

had demonstrated them to be failing so badly.

|

| Using cards to create sequential chains of events |

Thirdly, cards are immensely malleable in their use.

Considered carefully and creatively, one set of cards can be set to numerous

different tasks, of which sequencing in this case is just the first. And using

them to complete these varied tasks is key to students finding meaning from a vast

sea of events.

Finding

Meaning Among the Fragments

Armed with their own sets of cards, students were encouraged

(with the help of in-class modelling through the sequencing cards I had already

produced) to engage in a range of meaning-making activities to better process

and comprehend the big picture.

The first activity was to chunk events into different time

periods. Chunking (grouping together discreet pieces of data into larger

self-contained units) is a key process in memorisation anyway, meaning this

activity is vital to enable students to commit a very large number of events to

their long-term memory. Chunking events into particular time periods also gives

students the opportunity to consider what broader historical processes bind

together the events. Some are, of course, obvious: one very valid approach is

simply to group events by the ruler under whose reign they occurred. There are

other approaches which require greater consideration. For example, did certain

events happen within the same period of political oppositional activity,

economic growth or depression, or societal transformation? And if so, what can

they reveal about these periods? In short, the activity of periodisation is almost

limitless.

Another activity was, once they were comfortable with the

general order of events, for students to begin dividing them between the

different “themes” of the course (political, economic, social, and cultural).

This is not easy (and is not meant to be). Viewed from different perspectives,

the same event may well fit into two, three, or indeed all four of the themes.

Careful deliberation as to which each one belongs to and why is a key part of

this activity, enabling students to uncover the different potential layers of

meaning to the multiple events they have studied. This activity also helps

prepare students to consider which evidence might be relevant for exam

questions focused on particular themes in our course.

|

| Sorting cards by theme (the key, of course, is students developing their own explanations for their choice of theme[s] for each card) |

Repeated

Practice (and so back to timelines!)

In the end, however, as a revision resource “sequencing

cards” have their greatest use insofar as they allow students to repeat their activities

regularly so as to commit them to, and retrieve them from, long-term memory.

On the one hand, this may be a straightforward matter of

repeating the movement of cards into a certain order and certain groups until

it sticks. This is, as I’ve already suggested, a good argument for cards as a

format.

But there is also an opportunity to reconsider the role of

timelines here as well. Having placed cards into the correct chronological

sequences, students can then commit them to a series of static timelines on

paper, which can then be referred back to when testing their future efforts to sequence

the cards. These timelines can also be reproduced periodically as “knowledge

dumps” or “blurts”, allowing students to chuck their sequential and

chronological knowledge onto a page before checking for errors. These timeline

activities, I would emphasise, presuppose the continued and constant use of

sequencing cards, rather than superseding them as a resource, as only their

continued and constant use can ensure that students’ memory of the overall

chronology is maintained.

Summarising

An Approach

What does this all mean for the question I started off this

post with – that of ensuring students know the story of the course?

There are a few broad points I’d like to emphasise, whether

or not the particular approach outlined here is followed:

- students should be encouraged and actively supported to see the course as one whole narrative, rather than a series of facts or separate events;

- we should be prepared to draw up a “big picture” for students, but with the expectation that they actively use and manipulate this resource, rather than refer passively to it;

- effective use of any “big picture” resource requires students to continually pull it apart and reconstruct it in as many ways as useful for their understanding (and there are, I think, a great many useful ways of doing this);

- as teachers, we should view our role in this process as one of modelling and demonstrating how to students, and at the same time of challenging and inspiring them to find new ways of processing and reconstructing the “big picture” we have given them.

I hope this might be of some use to you and your students,

and would love to hear your thoughts on any of the ideas I’ve presented here!

This post refers to lesson resources developed for Year 13 students ahead of their exam for AQA 1H: Tsarist and Communist Russia, 1855-1964. All resources mentioned can be found here.

No comments:

Post a Comment