Revision is often the last thing we think about when planning a teaching unit. I remember vividly years where just getting to the end of a course felt like an achievement. But if students are to succeed in exams, a solid revision scheme is clearly important.

In his recent feedback webinar for the AQA A-Level History

exam’s component 1, Keith Milne raised a number of useful and provocative

points. Several things, in particular, struck me in relation to revision.

- Students should revise with a purpose – it’s not enough just to memorise information, they need to know why they need that information.

- Students must be able to use knowledge to reach a judgement, not just to demonstrate their memory of facts.

- Students need to have clear strategies to answer the question asked in exams, something requiring broad evaluative and analytical skills.

Here, I’ll give a few thoughts on how we might approach these points, with some examples to illustrate, and draw out two key principles from each. These are drawn from my experience of teaching the AQA course 1H: Tsarist and Communist Russia and my revision resources, which are linked in full here.

Revise

with a Purpose

This seemingly obvious point is actually deceptively

complex. Usually, we’re pre-occupied with getting students to “remember stuff”.

After all, what can you possibly do in an exam without knowing the relevant

information? The first thing to emphasise is that, self-evidently, knowing

information is important. One way or another, the first port of call when

starting revision is to check what students remember and fill in the gaps of what

they don’t.

But it’s equally important, especially if students are to

stretch themselves to writing higher-level answers in exams, to ensure they can

use information critically: sort it, categorise it, explain it, evaluate it,

and prioritise it.

One starting point for

this is to think about the big themes for a course. Teaching AQA’s 1H: Tsarist

and Communist Russia unit, the content fits broadly into four themes –

government and politics (including opposition and ideology), society, culture,

and economy. Rather than do a chronological reteach of everything we had

studied since the start of Year 12, I decided this year to break the course

into the four themes (combining society and culture) and focus on each with an

activity booklet.

In addition, I found that a large card sort summarising aspects of the key content to be a useful tool. Students can sort the cards into the four themes, then re-order chronologically. If this is to be done effectively, though, it must be repeated multiple times – understandably, having just finished two years’ of content, the first time students do this at the start of a period of revision they find it very difficult indeed. Each time becomes easier (a sign, I would argue, that the approach is working).

But why approach revision like this?

Firstly, if “memory is the residue of thought” (Willingham),

then getting students to think hard about information in revision, through

categories and themes, is a good way to get them to remember it. Secondly, critical

thinking and analysis is key to the exam. A point made in Milne’s webinar is

valuable. Students shouldn’t simply approach the exam as an opportunity to

regurgitate facts – their knowledge must be well-selected.

- Principle 1: Approach revision as “teaching” (not simply “revising”) and schedule in plenty of classroom time for it. Comprehensive revision requires the teacher in the room and should be built around meaningful exercise that get students to think. We shouldn’t just dump revision guides in front of students and expect them to meaningfully do it at home.

- Principle 2: Structure revision around clear objectives which require students to use information in a variety of ways and for a variety of purposes. In revision, we should think firstly about restructuring what students are learning, rather than repeat, in the same order as it was taught, all the course content.

Use

Knowledge to Reach a Judgement

What’s the point of writing an essay? (Actually, I think it’s

worth asking students this question throughout their A-Levels.) There’s really

only one – to make a clear, sustained, and substantiated argument. Milne

pointedly raised the frustration that examiners have with students sitting on

the fence – something he noted does not equate to a “balanced argument” (since,

without a judgement, where is the argument?).

Whichever style of question students have to answer in the

exam, a judgement somewhere will be needed. An important part of revision

should be to teaching students to reach the judgements that will frame their

entire piece of extended writing. This is not something we should expect

students to be able to do automatically – and, indeed, it is something we

should be doing throughout our course in Year 12 and 13.

Give students the tools to do this and make it a focus of

revision lessons once content is taught. There are a number of steps required

to making a clear judgement.

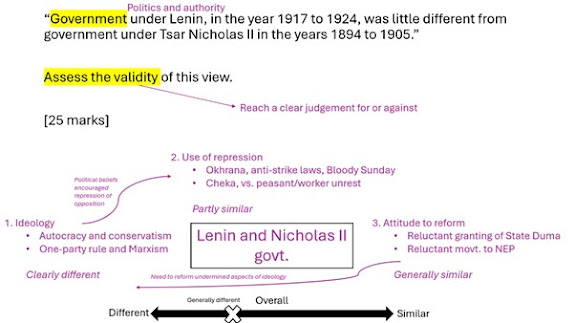

Firstly, what is the question actually asking students to

focus on? As a starting point, ask students to read the question carefully and

then identify which big theme(s) it relates to – it will usually link to one,

or at most, two of these.

Secondly, what are students going to focus on in their answer?

This requires more than a two-column agree/disagree table, an essay planning

approach that invites C-grade narrative answers. Instead, there should usually

be clear factors or areas of focus that should be discussed. Drawing these out as

a mind map, for example, is a quick a simple way to map out key ideas and draw

links between them.

Thirdly, what judgement will be reached on each area of

focus? Depending on what aspect of a question a student is writing about, a

different kind of judgement (or perhaps sub-judgement) will be reached. Each

factor might be judged separately first.

Finally, what overall judgement will be reached, having

considered each factor? A spectrum or continuum might allow a judgement with

nuance without leaving the student sitting on the fence.

- Principle 3: Focus on the planning of essay questions as much as the writing. Without getting this piece of procedural knowledge right, students won’t be able to begin tackling the substantive activity of writing adequately.

- Principle 4: Treat essay practice as a whole-class activity. Teachers in the room, and students themselves, should be in conversation about how to reach judgements on particular essay questions in order to hone their approaches and skills.

Answer

the Question

History is conceptualised through questions. They help focus

analysis and frame arguments. But Milne also made an interesting observation: within

a particular topic, there are only so many questions historians might really

ask.

His suggestion, that students think carefully about what the main questions for a topic actually are, is an excellent one. I asked my Year 13s to look back through the course we had taught, giving them our original enquiry questions, and generate their own big questions to go with them. Each one was to be linked to at least one of the main themes for the course

More than just the questions, I was impressed by some of students’ own reflections. Asked why this might have been a useful activity, one student replied: “To get us thinking thematically.” Another: “To help us conceptualise the big trends over time.” Yes and yes!

- Principle 5: Move beyond the formulaic procedural task of answering exam questions. It’s useful for students to understand the purpose of questions themselves to History as a discipline.

- Principle 6: Encourage students to see the History they are revising as a series of questions. If they can formulate (and answer) these, they have an underlying basis for understanding and responding to questions they will be asked in the exam.

No comments:

Post a Comment